In our series World Champion Born On This Date, today we shall see the life journey of a champion who is considered to be the ‘Father of the Modern Chess Strategy’. You guessed it right- he is Wilhelm Steinitz of Austria.

In the erstwhile Soviet Union, four prestigious Chess awards were conferred every year for excellence in Chess. The best attack award was named after the greatest attacking player of all times, Alexander Alekhine. Top defense award was called Lasker award, in memory of Emanuel Lasker, who possessed extraordinary skills in defense. The best endgame award was named after Jose Raul Capablanca, who had little difficulty in converting theoretically drawn end games in wins. Lastly, the strategy award was named after Wilhelm Steinitz, the first official World Chess Champion.

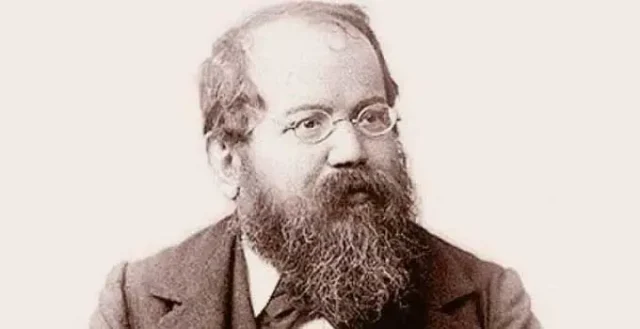

Wilhelm Steinitz– The Master of Strategic Chess

A Chess game played between two strong players, who have correctly grasped the important principles of Chess, usually takes a slower pace than a game between two amateurs. Since direct skirmishes are likely to fail early in the game, now-a-days the strong players choose to slowly mobilise all their forces, thereby, building up the position in a truly warfare style, before launching an attack.

This concept was first thought of in 1870s by Father of the Modern Chessz, who, after mastering the attacking and defensive skills of Paul Morphy, felt a need to look for something more concrete and complex than a direct violent attack from move one.

The Father of the Modern Chess came up with a new revolutionary concept with his words and famous quote “In the beginning of the game ignore the search for combinations, abstain from violent moves, aim for small advantages, accumulate them, and only after having attained these ends, search for the combination with all the power of intellect, because then (after strengthening the position by accumulating the small advantages) the combination must exist, however deeply hidden.” Though a controversial thought then, Steinitz was able to justify this strategy by defeating the best of the contemporary players.

Chess Life of Wilhelm Steinitz

Wilhelm Steinitz (May 14, 1836 – August 12, 1900) was born at Prague (now capital of Czech Republic) in the Bohemia state of Austrian Empire. He later moved to Vienna, the capital, to study mathematics. Around 1860, he became the strongest Chess player in the world and decided to move to England in 1862 to compete with the strong players.

Steinitz had a brilliant record of matches and tournaments for more than three decades. He became famous as The Austrian Morph in the 1860s for his brilliant attacking play. Though Steinitz solicited for slower attacking methods, he never disagreed with Morphy’s way of King side attack.

Steinitz’s match against Zukertort in 1886, in which the Chess Clock was used for the first time in history, is considered to be the first official match for the World Chess Crown. Steinitz became an American citizen in 1888. In 1894, he lost his world Chess throne to Emanuel Lasker of Germany. However, Steinitz continued to play brilliantly for a couple of years more after which his health deteriorated. He succumbed to various illnesses and passed away in New York.

Learn from the Champion

I have chosen a game played by Wilhelm Steinitz while he was on his decline and yet had not lost any knowledge or skills he had accumulated in four decades. This game has been annotated by almost all world champions and Chess writers.

Here is an example of how deeply he had grasped the essence of Chess. Let us see what Grandmaster Savielly Tartakower had to say about the game- “The feature of the following game is how White fastened on a small weakness in the enemy’s camp

and how, by skillful maneuvering, he prevented him from castling. Never relaxing his grip, he wound up the game with one of the most beautiful and aesthetically satisfying combinations ever devised on the chessboard”.

William Steinitz – Curt Von Bardeleben at Hastings International Masters (10) on 17.08.1895

Tartakower+J. du Mont+Reti+Anatoly Karpov+Praveen Thipsay

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Bc5 4.c3 Nf6 5.d4 exd4 6.cxd4 Bb4+ 7.Nc3

“A move already advocated by Greco the Calabrese in 1619, by which White offers to give up a pawn for

the attack.” -Tartakower

7…d5?!

“The usual and better course here is 7…Nxe4 ; though Black must not hope to hold the gain of the pawn.”-

Tartakower and Reti

8.exd5

“White has come out of the preliminary skirmish with a pawn in the centre. Even though it is isolated, this

pawn will prove a tower of strength”- Tartakower

8…Nxd5 9.0–0 Be6?!

“After this move which, to all appearances, is perfectly sound, Black loses his chance of castling. He should, at all cost, have played 9…Bxc3 , and then completed his development. 10.bxc3 0–0 11.Re1 , was necessary, though White stands much better.” -Reti

10.Bg5! Be7 11.Bxd5 Bxd5 12.Nxd5 Qxd5

12…Bxg5 is even worse. For example, 13.Re1+! Be7 14.Nxe7 Nxe7 15.Qa4+ Qd7 16.Qb4 etc.

13.Bxe7 Nxe7 14.Re1

“After this orgy of exchanges, Black finds himself unable to castle. With his next moves he tries to get his king into safety by ‘artificial castling,’ but it takes too much time”. -Tartakower

“The point of all the exchanges, as by this move White obtains command of the board, prevents Black from castling, and initiates a most powerful attack on the King.”- Tarrasch

14…f6 15.Qe2 Qd7 16.Rac1?!

“16.Rad1! would have been more accurate” — Anatoly Karpov. For example, if 16…c6? 17.d5! cxd5 18.Rxd5 Qc7 19.Nd4 when Black has no defensive possibility left.

16…c6?

“It would have been preferable to play 16…Kf7 , as White can’t embark on a combination with 17.Qxe7+ Qxe7 18.Rxe7+ Kxe7 19.Rxc7+ due to 19…Kd6! “- Tarrasch

17.d5!!

“A fine square vacating sacrifice. The d4 is made available for the knight, thus greatly intensifying the

attack”. -Tartakower

17…cxd5 18.Nd4 Kf7

“Black has almost castled, but not quite”.- Tartakower

19.Ne6 Rhc8

Now White wins now with a forced combination, exactly in the style Steinitz had quoted. A very difficult combination to spot though.

Now White wins now with a forced combination, exactly in the style Steinitz had quoted. A very difficult combination to spot though.

20.Qg4! g6 21.Ng5+! Ke8!

Black seems to have held his own as a few exchanges seem to be inevitable now. But the Austrian Morphy had already foreseen the end of the battle!

22.Rxe7+!!

“An amazing situation! All White’s pieces are ‘en prise’, and Black threatens …. ![]() xc1#. Yet he cannot take the checking rook, 22…

xc1#. Yet he cannot take the checking rook, 22…![]() xe7 23.

xe7 23.![]() xc8+

xc8+ ![]() xc8 24.

xc8 24.![]() xc8+, and White remains a piece ahead.”- Tartakower

xc8+, and White remains a piece ahead.”- Tartakower

“The variations resulting from 22….![]() xe7 show the astounding degree of precision, which was required of White’s calculations, before he could venture on the move in the text, e.g. 22….

xe7 show the astounding degree of precision, which was required of White’s calculations, before he could venture on the move in the text, e.g. 22….![]() xe7 23.

xe7 23.![]() e1+

e1+ ![]() d6 24.

d6 24.![]() b4+! ….

b4+! ….![]() c7 25. ♘e6+

c7 25. ♘e6+ ![]() b8 26.

b8 26. ![]() f4+ and wins. In this beautiful combination the rook remains ‘en prise’ for several moves until Black, compelled to capture it, succumbs to a mating finish”.- Tartakower

f4+ and wins. In this beautiful combination the rook remains ‘en prise’ for several moves until Black, compelled to capture it, succumbs to a mating finish”.- Tartakower

22…Kf8!

22…Kxe7 23.Re1+ (23.Qb4+ seems as strong.) 23…Kd6 24.Qb4+ Kc7 25.Ne6+ Kb8 26.Qf4+

23.Rf7+! Kg8!

[23…Ke8?? 24.Qxd7# Or 23…Qxf7 24.Rxc8+ Rxc8 25.Qxc8+ etc.

24.Rg7+! Kh8!

[24…Kxg7 25.Qxd7+ Or 24…Qxg7 25.Rxc8+ Or 24…Kf8 25.Nxh7+! Kxg7 26.Qxd7+

25.Rxh7+!

At this stage, Black, who himself was a strong Chess master, left the tournament hall without making a move. The rules of the game did not have a possibility of ‘resigning the game’ in those days. Steinitz, therefore, had to demonstrate the following winning line to the organisers before being awarded the full

point! (The tournament wasn’t being played with Chess clocks).

“Mr. Steinitz (at the time) demonstrated the following brilliant and remarkable mate in ten moves”.– Tarrasch

25.Rxh7+!

25…Kg8 26.Rg7+! Kh8 27.Qh4+! Kxg7 28.Qh7+ Kf8 29.Qh8+ Ke7 30.Qg7+ Ke8 31.Qg8+! Ke7 32.Qf7+ Kd8

It is Mate in three now.

33.Qf8+! Qe8 34.Nf7+! Kd7 35.Qd6#!

White doesn’t give Black a single chance to execute mate in one with ….Rxc1. A truly amazing combination.

Clic Here to read more stories.