In our series Champion Born On This Date, today we will see the life story of ‘The Iron Tiger’. You guessed it right! He is the 9th official World Champion Tigran Petrosian.

Tigran Petrosian- The Iron Tiger

Tigran Petrosian was orphaned in World War II. He had to sweep streets for making a living and became partially deaf due to exposure to cold weather. Yet he went on to play three consecutive World Championship Matches and Eight Candidates Championships. He was famous for his ‘Positional Exchange Sacrifices’ and was considered ‘The Toughest Player to Beat’. As a result, he earned the nickname ‘Iron Tigran’ which means ‘The Iron Tiger’.

Early Life

Petrosian was born to Armenian parents on 17th June 1929, in Tbilisi (present-day Georgia). As a young boy, he was an excellent student and enjoyed studying. As his father was illiterate, he wanted his son to study more. But, Petrosian started playing Chess from the age of eight.

Though he became an orphan, he continued to play Chess. An ardent Chess lover, he used his rations to buy books on Chess like Chess Praxis by Aron Nimzowitsch and The Art of Sacrifice in Chess by Rudolf Spielmann. At the age of 12 he began training at the Tifilis Palace of Pioneers under the coaching of Archil Ebralidze. Petrosian developed a repertoire of solid positional openings such as the Car0-Kann Defense.

Success Story of Tigran Petrosian

In 1946, Petrosian won the Armenian Chess Championship and the USSR Junior Chess Championship. He moved to Moscow in 1949, to boost his Chess career. He advanced rapidly with an improved results in the tournaments of Soviet Union.

Petrosian was placed second in the 1951 Soviet Championship, thereby earning the title of International Master. Later he earned the title of International Grandmaster after finishing a creditable second in the Stockholm 1952 tournament. Thus, he qualified for the 1953 Candidates Tournament.

Tigran Petrosian finished 5th in his maiden Candidates Tournament and gradually improved his results. In 1962, he qualified for his first World Championship match. against Mikhail Botvinnik. Petrosian won the match with a final score of 5 to 2 with 15 draws, thus, becoming the 9th World Champion.

Tigran Petrosian- The World Champion

In 1966, Petrosian was challenged by Boris Spassky. But, he defended his title successfully. During his World Championship reign, he studied for a degree of Master of Philosophical Science at Yeveren State University. His thesis, dated 1968, was titled ‘Chess Logic, Some Problems of the Logic of Chess Thought’.

At that time, he also campaigned for the publication of a chess newspaper called 64 for the entire Soviet Union, rather than just in Moscow.

However, Petrosian lost his World Championship crown to Boris Spassky in the match held in 1969. But, he remained at the top for another decade, even after losing his crown.

Petrosian died in Moscow on 13th August 1984. At the time of his death, Tigran Petrosian was working on a set of Chess-related lectures and articles to be compiled in a book. Those were later edited by his wife Rona and published posthumously as ‘Petrosian’s Legacy’ in Russian in 1989 and in English in 1990.

Learn from the Champion

Today we shall see a game by Tigran Petrosian which has been praised by several top players of different generations. Though Petrosian preferred to play slow positional games, he did not shy away from accepting the challenges the positions offered.

Tigran Petrosian, V (2640) – Robert James Fischer (2760) [D82]

Candidates Match Buenos Aires (2), 05.10.1971

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.Nc3 d5

Fischer’s favourite opening choice, the Grunfeld Defence.

4.Bf4

4.e3 was the alternative Petrosian preferred in his youth.

4.Bg5 is one of the variations named after Petrosian.

4…Bg7 5.e3 c5 6.dxc5 Qa5 7.Rc1!

7.Qa4+ Qxa4 8.Nxa4 is the boring option several players choose but Petrosian goes for the sharpest alternative.

7…Ne4 8.cxd5

[8.Nge2!?]

8…Nxc3 9.Qd2 Qxa2 10.bxc3 Qa5

10…Qxd2+ was tried in Karpov-Kasparov Match 1986. White stands slightly better.

11.Bc4 Nd7 12.Ne2 [12.Nf3!]

12…Ne5?

[12…Nxc5= was the right way.]

13.Ba2! Bf5?

[13…Qxc5 14.Nd4 was the more solid choice though Black does have some development problems.]

Robert James Fischer

Tigran Petrosian

14.Bxe5! Bxe5 15.Nd4 Qxc5

[Otherwise 16.c6.]

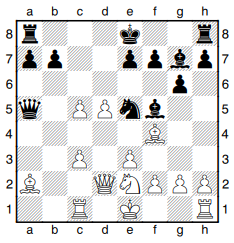

16.Nxf5 gxf5 17.0–0 Qa5!?

Robert James Fischer

Tigran Petrosian

Tigran Petrosian

18.Qc2!

[Again the sharpest! Perhaps Fischer expected the prophylactic 18.g3 for which Black can try 18…h5 19.Qc2 h4 20.Qxf5 Bd6 21.Bb1 Qc7 with counterplay.]

18…f4 19.c4 fxe3?!

[Better was 19…b6]

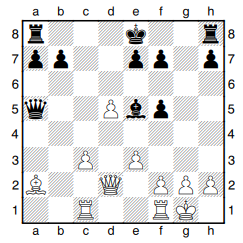

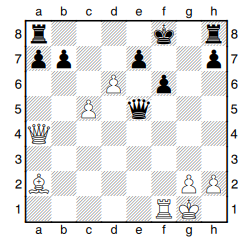

Robert James Fischer

Tigran Petrosian

Tigran Petrosian

20.c5!!

[20.fxe3 is not so strong as Black is able to block the WB with 20…Qc5]

20…Qd2! 21.Qa4+! Kf8

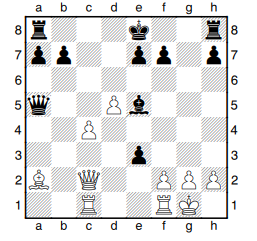

Robert James Fischer

Tigran Petrosian

Tigran Petrosian

22.Rcd1!!

[The only move to keep the advantage.22.fxe3? Rg8 is very dangerous.]

22…Qe2

[Not 22…e2? 23.Rxd2 Bxh2+ 24.Kxh2 exf1Q 25.d6 exd6 26.Qd7+–

Or if22…exf2+ then 23.Rxf2 Qh6(23…Bxh2+ 24.Kf1 Qg5 25.d6)24.d6! f6 25.dxe7+ Kg7 26.Qg4+ Qg6 27.Qe6 Rhg8 28.Rd8! and White wins.

22…Qb2? loses to 23.fxe3 Rg8 24.Rf2 Qc3 25.d6 Qxe3 26.dxe7+ Kg7 27.Bxf7]

23.d6! Qh5

[23…exf2+ loses to24.Rxf2 Bxh2+ 25.Kxh2 Qxf2 26.dxe7+ Kg7

(26…Kxe7 27.Rd7+ Kf828.Qc4+–)

27.Qg4+ Kf6(27…Kh6 28.Rd5)28.Rd3 Kxe7 29.Qd7+ Kf8 30.Qd6+ Kg7 31.Rg3++–

Or if 23…exd6 then 24.fxe3! Qxe3+ 25.Kh1 f6 26.Qd7+–

23…Bxh2+ was inadequate too. 24.Kxh2 Qh5+ 25.Kg1 e2 26.dxe7+ Kg7 27.Qd4+ f6 28.Rd3 exf1Q+(28…Qh1+ 29.Kxh1 exf1Q+ 30.Kh2)

29.Kxf1 Qh1+ 30.Ke2 Qh5+ 31.Kd2 Qh6+ 32.Kc3 Rhe8

(32…Qc1+ 33.Kb3)

33.Rh3! Qg6 34.Rg3]

24.f4 e2

[24…Bf6 loses to25.Rd5 Qg6 26.f5 Qh6 27.Qb3 e2 28.Re1 Qf4 29.dxe7+ Kg7 30.Rxe2 Bd4+ 31.Rxd4 Qxd4+ 32.Kf1 Qf4+ 33.Rf2 Qc1+ 34.Ke2+– etc.]

25.fxe5 exd1Q 26.Rxd1 Qxe5

[26…Kg7 27.Rf1 e6

(27…Qxe5 28.Rxf7+ Kh6 29.Qh4+ Kg6 30.Rxe7+–)

28.Bxe6+–]

27.Rf1,f6

[27…f5 loses to28.Qb3 Kg7 29.Qf7+ Kh6 30.dxe7+–

27…Qxc5+is no better. 28.Kh1 f6 29.Qb3 Kg7 30.Qf7+ Kh6 31.dxe7]

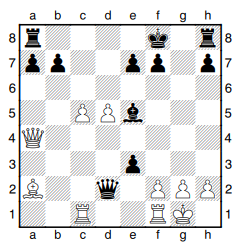

Robert James Fischer

Tigran Petrosian

Tigran Petrosian

28.Qb3! Kg7

[28…e6 29.Qxb7 Re8 30.c6]

29.Qf7+ Kh6 30.dxe7 f5 31.Rxf5 Qd4+ 32.Kh1 [Black resigned.]1–0