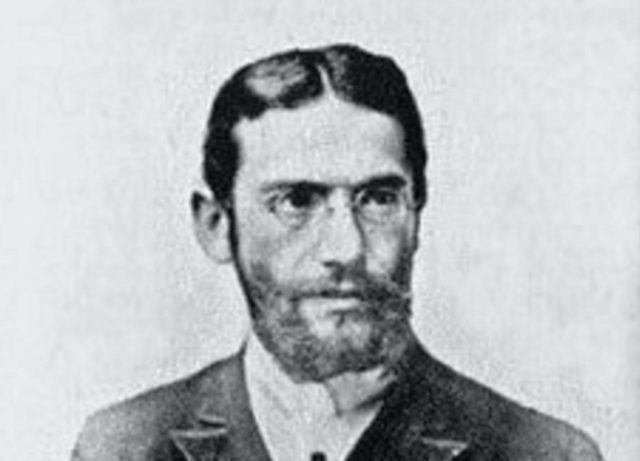

In our series ‘The Uncrowned Kings’, today we will see the story of Dr Siegbert Tarrasch, the Chess Master who dominated the Chess world for two decades.

Dr. Siegbert Tarrasch- A Doctor & a Chess Player

Dr. Siegbert Tarrasch was born on 5th March, 1862 at Breslau (now in Poland) to Jewish parents. In 1880, he finished his school and moved to Berlin to study medicine. He became a successful medical practitioner initially in Bavaria and later in Munich.

Being an avid Chess player, Tarrasch took part in tournaments and one-one matches. He won four major tournaments (Breslau 1889, Manchester 1890, Dresden 1892 and Leipzig 1894). In the midst, he drew his match against Mikhail Tchigorin at St. Petersburg in 1893.

Tarrasch scored heavily against the ageing World Champion William Steinitz in tournaments (+3−0=1). But he refused an opportunity to challenge the latter for the World Title in 1892 because of the demands of his medical practice.

In my opinion, had he agreed to play the match, he would have figured in our 2024 series ‘World Champion Born On This Date’ as the Second Official World Champion.

Tarrasch remained a powerful player, demolishing Frank James Marshall in a match in 1905 (+8−1=8), and winning Ostend International 1907 ahead of Schlechter, Janowski, Marshall, Burn and Tchigorin.

Lasker-Tarrasch Rivalry

However, Dr. Siegbert Tarrasch could not match Emanuel Lasker. Fred Reinfeld wrote, “Tarrasch was destined to play second fiddle for the rest of his life.”

There was no love lost between Tarrasch and Lasker. The story goes that when they were introduced at the opening of their 1908 championship match, Tarrasch clicked his heels, bowed stiffly, and said, “To you, Herr (Mr.) Lasker, I have only three words, Check and Mate” and left the room. Lasker beat Tarrasch convincingly in the match +8−3=5.

Dr Siegbert Tarrasch played his second World Championship match against Dr Lasker in 1916, during the World War I but lost heavily with no wins, five losses & just one draw.

Dr Siegbert Tarrasch- The Chess Writer

Tarrasch was a very influential Chess writer, and was called Praeceptor Germaniae, meaning “Teacher of Germany.” He wrote several Chess Books and Articles, found various systems and defences of play & was regarded as the ‘Best Player in the World’ by his fans.

He took some of Wilhelm Steinitz’s ideas such as Control of the Centre, superiority of a Bishop over Knight in open positions and made them more accessible to the average Chess Player. He emphasised on piece mobility and space advantage. He disapproved of strange ideas of aging Steinitz, such as accepting cramped positions, saying that they had ‘the germ of defeat.’

Tarrasch formulated a very important rule in Rook Endgames ‘Rooks behind Passed Pawns’ which finds place in every Endgame Book.

Though the ‘hypermodern players’ criticised Tarrasch of being ‘dogmatic’, there was no truth in it. It is true that Tarrasch had bad results against Dr Lasker, Rubinstein & Dr. Alekhine, it was not due to dogmatism but simply because most of these losses were after he had turned 50 years of age.

In fact, David Bronstein, in his book on the King’s Indian Defence, mentions that the great idea of this hypermodern defence was the brainchild of Dr. Tarrasch. In ‘My Great Predecessors’, Garry Kasparov has refuted all the criticism against Tarrasch and has acknowledged huge contribution of the latter to modern Chess.

This great Chess author passed away at Munich on 17th February, 1934, leaving behind a great legacy of his evergreen Chess Strategy & Openings.

Learn from the Master

Today I have chosen a great game by Dr Tarrasch, not only for it’s beauty but also because it was the first Tarrasch game I saw, over 50 years ago, in Fred Reinfeld’s ‘100 Best Brilliancy Prize Games’.

As a child, I was indeed fascinated by Tarrasch’s play. Though the game got 1st Brilliancy Prize, not many authors have chosen to publish it in their books, for various reasons.

This game is an excellent example of the supremacy of Paul Morphy’s way of playing over the superficial hypermodern Chess. The game shows that although Dr Tarrasch was already on his decline, he had not forgotten the basics of Chess. I must add that I am still as fascinated by the game as I was, when I saw it as a beginner.

Aron Nimzowitsch – Siegbert Tarrasch [D05]

St Petersburg International Preliminary (5), 28.04.1914

1.d4 d5 2.Nf3 c5 3.c4 e6 4.e3 Nf6 5.Bd3 Nc6 6.0–0 Bd6 7.b3 0–0 8.Bb2 b6

A common balanced position from Semi-Tarrasch Defence of the Queen’s Gambit declined has been reached.

9.Nbd2

A strange move, placing a Knight on a square which has no future due to Black Pawn on ‘d5’. If White wanted to play against the ‘Hanging Pawns Structure’, he should have either made Pawn exchanges in the centre followed by placing the QN at ‘c3’ from which it will directly attack one of the Hanging Pawns. It was also good to develop the QN to ‘c3’ immediately.

9…Bb7 10.Rc1 Qe7 11.cxd5 exd5! 12.Nh4 g6!

Black is not worried about the weakness on the a1–h8 diagonal as White has neither enough piece activity nor adequate centre control to give any threats.

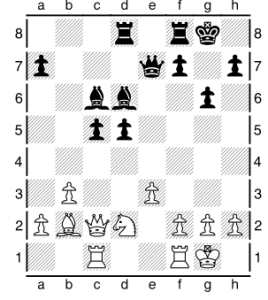

13.Nhf3 Rad8 14.dxc5 bxc5

Tarrasch

Nimzowitsch

A standard ‘Hanging Pawns’ position has arisen. White has the ‘treasure’ of hypermodern principles — no Pawn weakness. Black has the treasure of preachings of Paul Morphy. Black has better activity of pieces, more space and better development.

15.Bb5!

The only good move played by White in this game. White wants to create threats along ‘c’ file.

15…Ne4 16.Bxc6?

This arbitrary, unprovoked capture, however, is not in keeping with the previous move. It is basic violation of Steinitz’s Principles as well. The logical follow up would have been Prophylactic 16.Re1 followed by eventual Nf1, keeping the King side well defended. Better was 16.Re1! f5 17.Nf1 with an unclear position.

16…Bxc6 17.Qc2?

This moves suggests lack of sense of danger & over-confidence in correctness of the superficial hypermodern principles. Black’s pieces are powerfully placed for an offensive against King side. However, White seems to be busy with his hypermodern manoeuvre. Prophylactic 17.Re1! followed by Nf1 was called for.

17…Nxd2!

A fantastic, unexpected move, exchanging the ‘seemingly most powerfully placed’ piece, but fully in the spirit of an important Chess Principle by Tarrasch — “It doesn’t matter which piece is exchanged with which one. What matters is what is left on the ChessBoard!” The exchange leaves White with an ‘extremely weak King side’ due to the absence of a Knight on ‘f3’. Three centuries before this game, Greco had taught that the best defensive pieces in a ‘King side castling’ were Knights on ‘f3’ (for White) and ‘f6’ (for Black).

Black correctly senses that the preparation for attack is over and now it is the time to strike hard.

18.Nxd2

Forced. 18.Qxd2? loses to 20….d4! 19.Qe2 Rfe8! When White in a hopeless position. For example, 20.Rcd1 20…d3 21.Rxd3 Bxf3 22.gxf3 Qh4 23.Rxd6 Rxd6 24.Ba1 Red8 25.Qb2 f6!–+ etc.

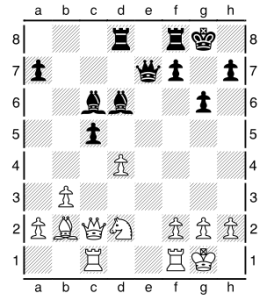

Or if 20.b4, then 20…. d3 21.Qd1 d2! 22.Nxd2 Qg5 23.g3 and we have the following position :–

(A possibility in the game, a variation.)

Tarrasch

Nimzowitsch

Black wins with 23…Bxg3! 24.fxg3 Rxe3 25.Rf2

(25.Rc3 Rxc3 26.Bxc3 Qe3+ 27.Rf2 Qxc3)

25…Qd5 26.Rf3 Rd3 27.Bc3 cxb4 28.Qb3 Qxb3 29.Rxd3 Rxd3 30.Nxb3 Rxc3 etc.

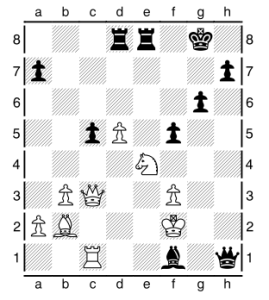

Now, back the actual game, after 18.Nxd2

Tarrasch

Nimzowitsch

The game went 18…d4!!

White has violated all the Classical as well as Hypermodern Chess Principles. In absence of a Knight on ‘f3’ White has absolutely no forces to guard his King against Black’s pieces.

19.exd4?

Nimzowitsch introduced the great principle of ‘Prophylaxis’ in his preachings. However, in my opinion, ‘Defending against the immediate threats’ is more important than taking hypermodern long-term prophylactic measures. Perhaps White believed that Black had blundered away a Pawn.

Tarrasch

Nimzowitsch

19.g3! reducing impact of the Black King Bishop was necessary. Black would have probably carried on his offensive with 19…Ba8! 20.exd4 cxd4 with dangerous threats. The ‘d4’ Pawn is taboo. 21.Bxd4? Ba3 22.Bb2 Bxb2 23.Qxb2 Qe2 24.Rcd1 Rxd2! 25.Qxd2 Qf3 etc.

19…Bxh2+! 20.Kxh2 Qh4+ 21.Kg1 Bxg2! 22.f3

White refrains from capturing the Bishop but the move chosen is even worse. 22.Kxg2 loses brilliantly to 22…Qg4+ 23.Kh2 Rd5 24.Qxc5 Rh5+! 25.Qxh5 Qxh5+ 26.Kg2 Qg5+! 27.Kh1 Qxd2 etc.

22…Rfe8!

Threatening ….Re2, forcing mate.

23.Ne4

23.Nc4 loses to 23….Qh1+ 24.Kf2 Bxf1 25.Rxf1? Qh2#!

23…Qh1+ 24.Kf2 Bxf1! 25.d5

25.Nf6+ would have been adequately met with 25…Kh8! 26.Nxe8 Qg2+ 27.Ke3 Rxe8+ 28.Kf4 g5+ 29.Kf5 Qxf3+ 30.Kxg5 f6+ 31.Kh6 Qh3#.

Or if 25.Rxf1?, then 25…. Qh2+ 26.Ke3 Qxc2 27.Rf2 cxd4+ etc.

25…f5!! 26.Qc3?!

26.Nf6+ Kf7 27.Nxe8 Qg2+ 28.Ke3 Rxe8+ 29.Kf4 g5+ was equally hopeless anyway.

Tarrasch

Nimzowitsch

26…Qg2+ 27.Ke3 Rxe4+! 28.fxe4 f4+!?

The Prettiest but not the Best.

28…Qg3+! would have checkmated quicker. 29.Kd2 Qf2+ 30.Kd1 Qe2#

28…Qxe4+! would also have lead to a quicker checkmate. 29.Kf2 Qg2+ 30.Ke3 Re8+ etc. But the variation played is more artistic.

29.Kxf4 Rf8+ 30.Ke5

30.Ke3 allows 30….Rf3#

30…Qh2+! 31.Ke6 Re8+! 32.Kd7

32.Kf6 leads to 32….Qf4#

32…Bb5#!

0–1

White has been checkmated, not a common occurrence in top games. It has been said that Nimzowitsch touched his King and tried to move it before realising that he had been checkmated. A great triumph of Classical theory over artificial & superficial ‘hypermodern’ play.

My advice to the readers is ‘The game of Chess is all about checkmating your opponent and our games should revolve around this basic idea of Chess.’